Summary in the Video

Explanation in the video

The ‘Overview, Summary, or Conclusion’ of this article can be found at the beginning of the YouTube video, so please refer to it.

If possible, we would appreciate it if you could subscribe to our channel to help maintain the site. It serves as motivation for us!

Introduction

This video series is structured around four major works by Émile Durkheim:

- The Division of Labor in Society (1893)

- The Rules of Sociological Method (1895)

- Suicide: A Study in Sociology (1897)

- The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)

First, the main topics regarding The Division of Labor in Society are as follows.

This video will focus especially on the topics related to solidarity and types of society.

The remaining topics will be covered in the next article.

- Chronology

- What are the bonds that connect people to one another?

- What is division of labor and what are its functions?

- Why does division of labor produce social solidarity?

- [Column] What is sociology? (This marks the end of the first article.)

- The difference between mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity(This marks the end of the second article.)

- The difference between segmentary society and organized society

- Collective conscience and collective representations

- [Column] What is sociological theory?

- Examination of solidarity: repressive law and restitutive law

- Non-contractual elements in contracts

- A society without crime is unhealthy

- [Column] Durkheim’s critique of Tönnies

- Is individualism detrimental to solidarity?

- Coercive division of labor and anomic division of labor

- Intermediate groups as a measure against the adverse effects of modernization

What Are Mechanical Solidarity and Organic Solidarity?

Society existed even before the development of the division of labor.

The division of labor is generally understood as a modern phenomenon, and in premodern societies, its scope was limited and relatively simple.

Nevertheless, even in premodern societies, forms of social solidarity (bonds) existed. In other words, we must distinguish between solidarity that emerges independently of the division of labor and solidarity that results from it.

This distinction forms the basis for understanding the difference between mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity.

POINTMechanical Solidarity:A form of social solidarity made possible by the similarity of individuals in terms of their values, lifestyles, and types of labor.

It typically occurs in traditional or less differentiated societies, where individuals share common beliefs and perform similar work.

POINTOrganic Solidarity:A form of social solidarity made possible by the differences among individuals in terms of their roles, values, and lifestyles.

It emerges in more complex societies, where people perform specialized tasks and depend on each other to maintain social cohesion.

When I first began studying sociology, I was puzzled by these two forms of solidarity.

First, I wondered: if solidarity can arise both from similarity and from difference, then why is the division of labor even necessary?

Second, the phrase “a cog in the machine” evoked, for me, a very modern image. So I instinctively assumed that modern society must be characterized by mechanical solidarity, not organic solidarity.

First, mechanical and organic solidarity can be difficult to understand if we assume that all other conditions remain the same except for the form of solidarity itself.

For example, modern societies generally have larger populations and higher levels of mobility than premodern ones.

It is reasonable to assume that in order to avoid being invaded by other countries, or to develop industries, military capacity, and cultural achievements, some degree of division of labor becomes indispensable.

In short, there is an element of necessity. We simply have no choice.

If everyone were leisurely engaged in hunting or farming, the nation might not survive. It becomes a matter of survival.

Thus, the need for the division of labor arises not from personal preferences or individual tastes, but from social imperatives.

Given this broader social context, it becomes clear that the two forms of solidarity are no longer functionally equivalent.

The idea of “having no choice” reminds me of what I learned from Max Weber about the development of capitalism.

At first, Protestants may have expanded their businesses based on religious motives. For example, they believed that earning wealth correlated with assurance of salvation after death.

However, over time, the sense that they had no choice but to continue this path became increasingly dominant.

Religious motives gradually fade away, and people become consumed by competition with others.

To avoid falling behind or to satisfy desires, they repeatedly invest and pursue rationalization.

When a country’s technological capabilities develop, other countries imitate or strive to advance in order not to be left behind.

In this way, the division of labor progresses globally.

In the modern society we live in today, the idea that “we can manage without division of labor” is probably too optimistic.

If we tried that, this country could not be sustained. We have no choice but to engage in division of labor.

Just as Weber compared bureaucracy to a rigid cage or shell, there exists a social force that constrains and regulates us.

Of course, even if that is the case, it does not mean that any particular economic or political system is always absolutely correct.

A new system of necessity may emerge in the future.

Karl Marx emphasized class struggle and revolution as forces that drive new systems.

It is also important to consider what Durkheim emphasized in this regard.

Causes of the Development of the Division of Labor

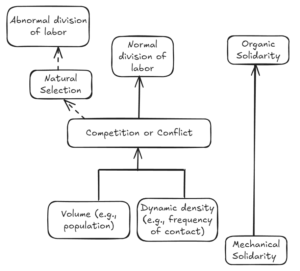

According to Durkheim, the cause of the development of the division of labor lies in the “increase in the volume of society and its dynamic or moral density.”

The key point is that it is a social cause, not a personal cause such as an individual’s desire to increase happiness or improve efficiency.

The increase in the volume of society means a quantitative growth such as population size and density.

The increase in dynamic density refers to a rise in the frequency and intensity of interactions among members of society.

According to Durkheim, when the population grows and people perform the same type of labor, competition for survival intensifies.

For example, even if the population increases, the amount of farmland does not increase accordingly, and the number of people who can use farmland is limited.

Therefore, to alleviate such competition, people diversify and create different divisions of labor themselves.

It can be said that this is an era where what one should do is not predetermined within a narrow set of options, but where individuals create their own choices.

However, strictly speaking, this is not a teleological explanation that “the purpose was to alleviate competition,” but rather a causal and consequential explanation that “it had the function of alleviating competition.”

This is because Durkheim clearly criticized teleological functionalism.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the increase in the division of labor did not simply alleviate competition but also contained elements that intensified competition.

This is easily understood by considering how restaurants in our society often quickly go out of business.

Durkheim also recognized that such intensification of competition could lead to anomie or the dysfunction of the division of labor, such as abnormal forms of labor division.

This can be illustrated with the following image.

To put it very simply, those who have lost, those who are forced into specific roles, and even those who have won but think excessively about themselves tend to experience a mismatch between their desires, which are excessively high compared to their current situation, and their ability to realize them.

Such abnormal tendencies tend to have a negative impact on social solidarity.

Of course, it is important to be keenly aware that the definitions and distinctions between winning and losing, or normal and abnormal, are not simple or straightforward.

Furthermore, Durkheim also holds the (meritocratic) perspective that some form of regulation is necessary when inequality arises due to discrimination based on factors other than ability, such as origin or kinship.

It is also necessary to consider the concept of habitus (cultural capital), proposed by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002), when thinking about equality.

For example, children raised by highly educated parents tend to achieve high educational attainment themselves.

This is related not only to economic capital but also to various forms of cultural capital, such as reading habits, appreciation of the arts, and social interests.

Therefore, simply making university education free does not easily resolve the issue.

Let us briefly summarize.

The cause of the development of the division of labor is the increase in social volume and dynamic density, and the reason why division of labor produces social solidarity is the increase in mutual interdependence.

The concept of organic solidarity, in which individuals are different and therefore mutually dependent and socially integrated, is understandable.

However, a straightforward question arises: “Why was social solidarity possible in pre-modern societies even though individuals were not different?” and “Did pre-modern societies lack mutual interdependence in the first place?”

If we were to make a simple conjecture here, it would be explained similarly to how “the form of solidarity is different but it is still solidarity,” as “the form of mutual interdependence is different but it is still mutual interdependence.”

Mutual interdependence also existed in pre-modern societies, but due to population growth and other factors, the traditional forms of mutual interdependence could no longer be maintained, and therefore had to transform into new forms.

In pre-modern societies, mutual interdependence and solidarity were characterized by close relationships among people. The physical distance was short.

This brings to mind Georg Simmel’s discussion about appropriate distance and freedom.

In societies without the internet or automobiles, interactions were limited to family, relatives, and neighbors.

The quality and form of mutual interdependence were different. The distance of interdependence was close and concrete.

In modern and contemporary societies, the key point is that relationships are distant and abstract.

For example, when shopping on Amazon, people have an abstract relationship in that they do not really know who is selling, who is making the products, or how they are made.

Similarly, most people living in cities do not know much about their neighbors.

A society that maintains social life only within close distances and limited circles can no longer be sustained,

and it inevitably becomes a society where people maintain relationships over long distances and with a wide range of others.

If we imagine a situation where buying and selling goods is possible only with people nearby,

we can easily foresee how inconvenient life would be.

For example, it is easy to understand if we think about farmers who produce crops not only for people in their local area but also for people all over the country whom they do not even know.

Of course, as the term globalization indicates, human relationships have extended to a global scale.

Most of us depend on others for almost everything necessary to live.

Emphasizing the aspect of “having no choice but to do so” gives a deterministic impression, but actually, listening to Durkheim’s arguments makes one feel that way.

Durkheim tends to emphasize social forces rather than individual subjectivity or will.

One might metaphorically think that, just as dinosaurs became extinct due to changes in the natural environment, it is difficult to go against social tendencies.

However, it should be noted that Durkheim also believed that while it is difficult for an individual alone, society can be transformed by the power of a collective (collective effervescence).

In societies where mechanical solidarity is dominant, the members’ individuality is almost nonexistent, which is an important point.

This is because similarity is emphasized more than differences between people.

Durkheim even described it as “solidarity possible only insofar as individual personalities are entirely absorbed into the collective personality.”

In other words, such a society cannot be maintained if each person strongly possesses individuality.

For example, individuality such as being skilled at hunting or farming might have existed in traditional societies.

However, in modern society, the degree to which individuality such as homosexuality, being non-religious, having flashy hair, or not participating in drinking parties is tolerated is relatively low.

Such individuality tends to be seen as something that breaks the group’s bonds, connections, and solidarity.

(Of course, the tolerance for these elements varies across different societies.)

Just as there are people in modern society who are not tolerant of such individuality, it can be said that our society is maintained to some extent through mechanical solidarity.

The slogan “Be an individual” is popular, but as mentioned earlier, such individuality tends to be subject to criticism and exclusion.

It is easy to understand if we look at celebrities who are criticized by the media over small matters.

No matter how much freedom there is, just as no one would wear a flashy suit to a solemn funeral, many cases are bound by homogeneity.

Of course, there are differences depending on the country and society.

In Japan, the sense of cooperation is strong, as seen in the saying “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down.”

In the United States, individuality and independence are emphasized, with a strong sense of self-responsibility developed through competition.

In the United Kingdom, tradition, class, and restrained expression tend to be valued.

In any case, the point they share is that norms about “how humans should be” are imposed on individuals.

John Stuart Mill argued that “individual freedom must not infringe on the freedom of others.”

If this balance is lost, social forces may trap people in a “double bind“, so caution is necessary.

Some people might go mad by receiving contradictory commands such as “be individual” and “do not be individual.” The concept of double bind was proposed by G. Bateson.

Although the development of division of labor has indeed increased freedom and individuality, not all freedom or individuality is allowed, and there is an appropriate range that exists in each society.

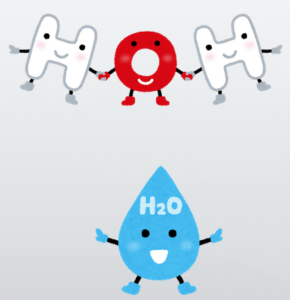

Why is solidarity described as “mechanical”?

It seems to be because “just like the molecules of an inorganic object, the whole can move only as long as each part does not perform its own distinct motion.”

For example, consider oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen.

If oxygen does not perform its usual function as oxygen but instead acts with individuality and takes on the function of fluorine ,then water cannot remain stable.

(This is merely a metaphor, so we will set aside its real-world feasibility.)

This is because the substance called water requires oxygen to fulfill its fixed role as oxygen.

Allowing freedom or individuality such as wanting to become another element would prevent the inorganic substance H2O as a whole from being maintained.

On the other hand, oxygen can be replaced by another oxygen atom due to its similar function, which is also an important point.

Similarly, in mechanical solidarity, individuals need to be similar, must not be individualistic, and have a high degree of substitutability.

Similarly, it is like when one gear in a machine suddenly develops individuality and causes the entire system to break down.

This is a metaphor for people being closely connected to each other, just as machine parts fit together to perform a single function.

However, even in societies with developed division of labor, individuals are often called “gears in a machine,” so I was confused at that time.

That said, I do not know whether Durkheim actually used the expression “gears in a machine.”

The point is that when I hear “mechanical solidarity,” I tend to associate it with the idea of “gears in a machine.”

For example, jobs such as those for public servants, where individuality is hardly allowed, or simple, repetitive tasks are similar cases.

Nowadays, many jobs are considered easily replaceable, like “gig jobs” or short-term side jobs, while others are hard to replace.

It can be said that jobs demanding creativity, problem-solving abilities, the establishment of complex human relationships, advanced expertise, and strategic thinking are hard to substitute.

Why is solidarity described as “organic”?

Organic substances generally refer to compounds that contain carbon.

Things with life, so to speak, are made up of organic matter.

In contrast, inorganic substances do not contain carbon.

The important difference is that inorganic substances have relatively simple structures, while organic substances tend to have complex structures.

For example, water, salt, and diamond are inorganic, whereas sugars and proteins are organic.

Durkheim sometimes compared society to the body of a human or an animal.

Just as the heart, stomach, brain, and other organs cooperate and work together to sustain the body, society too is sustained by people who are connected through solidarity, each fulfilling their own specific role.

Water, due to its simple structure, cannot perform complex functions.

However, it is precisely because of its simplicity that it becomes replaceable and easily maintainable.

Humans, with their complex structures, are capable of engaging in complex activities and sustaining themselves.

However, it is precisely this complexity of consciousness that also brings the risk of total annihilation through something like nuclear war.

The heart, unlike hydrogen or a mechanical part, cannot be easily replaced.

In the same way, an individual can become like a heart in a group—someone who is difficult to replace.

For example, it is similar to how the collective strength of a soccer team can drop significantly when its star player is removed.

One might think, “Just bring in a new star,” but it is not that simple.

The combination and coordination within the team are based on accumulated interactions, forming a complex ability that the players internalize almost bodily.

References

Recommended Readings

Emile Durkheim「The Division of Labor in Society」

Emile Durkheim「「The Division of Labor in Society」

DK Publishing, Sarah Tomley「The Sociology Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained (DK Big Ideas) (English Edition)」

About the Japanese version of this article

This article is a translation of an article written in [https://souzouhou.com/2024/11/27/durkheim-4-1/]. For detailed references, please refer to this link.

Comments