Summary in the Video

Explanation in the video

The ‘Overview, Summary, or Conclusion’ of this article can be found at the beginning of the YouTube video, so please refer to it.

If possible, we would appreciate it if you could subscribe to our channel to help maintain the site. It serves as motivation for us!

Introduction

This video series is structured around four major works by Émile Durkheim.

- The Division of Labor in Society (1893)

- The Rules of Sociological Method (1895)

- Suicide: A Study in Sociology (1897)

- The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)

First, here is the overall structure of Durkheim’s The Division of Labor in Society.

This article focuses specifically on repressive law and restitutive law.

The remaining topics will be discussed in the next video.

If you find this video helpful, please consider subscribing to the channel. It will motivate me to create the next one.

- Chronology

- What are the bonds that connect people to one another?

- What is division of labor and what are its functions?

- Why does division of labor produce social solidarity?

- [Column] What is sociology?

- The difference between mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity

- The difference between segmentary society and organized society

- Collective conscience and collective representations

- [Column] What is sociological theory?

- Examination of solidarity: repressive law and restitutive law

- Non-contractual elements in contracts

- A society without crime is unhealthy

- [Column] Durkheim’s critique of Tönnies

- Is individualism detrimental to solidarity?

- Coercive division of labor and anomic division of labor

- Intermediate groups as a measure against the adverse effects of modernization

How can labor-based solidarity be examined?

The difference between internal and external facts

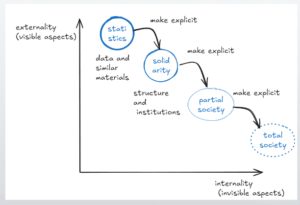

A moral phenomenon like social solidarity is inherently difficult to observe directly. Social solidarity itself is a type of internality, meaning it is not directly visible. Therefore, it is necessary to approach internal aspects by examining external facts, which are more easily observable.

It is essential to recognize that both external facts and internal facts are considered social facts as defined in The Rules of Sociological Method.

This approach is characterized by the principle of explaining society through society itself. More precisely, it is an attempt to grasp the invisible, total society indirectly by analyzing the partial aspects of society that are visible to us.

Even a partial society is, of course, difficult to observe directly. Concepts such as the social, collective existence, collective consciousness, and internal facts belong to the same group of meaning. Similarly, collective representations, external indicators, and external facts form another group.

Distinguishing between these two groups brings greater conceptual clarity. What is crucial is that both groups are regarded as social facts.

For example, organic solidarity and organized society are internal facts, but they are only one of the elements that constitute society or a partial whole.

In this sense, compared to society itself, which is the most abstract, broad, and complex, these elements are more visible. However, statistics and laws may be considered clearer examples of external facts because they are more concrete.

Society itself is the least visible, solidarity is more visible, and statistics and institutions serve to make that solidarity more observable.

For example, organized society can be considered a partial society in a certain sense, while a larger total society may include organic society and possibly other types of societies.

Through these interactions, society itself—the total society—is constituted. More specifically, Durkheim classifies social phenomena into those with organized forms and those without organized forms, such as social currents, in The Rules of Sociological Method.

In the case of the former, organized forms include examples such as rules, morals, language, and financial institutions. The latter, unorganized forms, refer to social currents such as society’s tendencies toward suicide or marriage.

Additionally, there are more objectively observable factors like population density and geographical features.

Examining types of solidarity through types of law

The difference between repressive law and restitutive law

The answer to the question “How can solidarity based on the division of labor be examined?” is, in abstract terms, through external indicators—external facts and collective representations—and, more concretely, through law. However, the question remains: what aspects of solidarity are examined by law, and how?

Durkheim analyzed two types of law as follows:

POINTRepressive law:a type of law focused on punishment to prevent crime and enforce norms. Examples include criminal law such as homicide and drug control laws.

POINTRestitutive law:a type of law aimed at restoring relationships and social order. Examples include civil law, commercial law, and constitutional law used to resolve contract breaches and family disputes.

- In societies where repressive law is dominant, mechanical solidarity is considered to be the prevailing form of solidarity.

- In societies where restitutive law is dominant, organic solidarity is considered to be the prevailing form of solidarity.

In this way, visible external facts such as law are used to indirectly grasp less visible internal facts such as solidarity. By classifying law, Durkheim conceptualizes a classification of social solidarity.

Why do different types of law correspond to different types of solidarity?

Consider a case where an act is regarded as a crime because it threatens a certain form of social solidarity.

For example, murder or violence can be seen as acts that break the bonds between people. Such acts are considered crimes, and the offenders are often subject to punishment. The purpose of punishment is to make the offender atone for their guilt and to deter others from committing similar acts that damage social bonds.

One might question whether this has not been generally true in all societies from ancient times to the present.

The issue is not simply the presence of repressive law, but rather the degree or intensity of its application. Consider repressive laws that punish theft with execution or whipping.

Why are the penalties so severe, and why are they more dominant than restitutive laws?

This is because, as seen in mechanical solidarity, people are bound together by homogeneity. Like the saying “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down,” those who differ are singled out and punished excessively in an effort to enforce sameness.

Some argue that the existence of the death penalty reflects the relatively strong presence of mechanical solidarity.

Durkheim explains that when a crime occurs, everyone experiences a collective feeling of outrage.

This anger is not the anger of any specific individual, but a public indignation shared by all. Since everything has been attacked, everyone collectively retaliates against this assault on the collective consciousness.

Considering that anger toward crimes not directly related to oneself in internet comment sections also falls under this type, such anger, when not excessive, can function positively as social sanction within society.

In premodern societies, this consciousness was stronger than in modern societies, and the intensity of anger was greater. Because people were more similar to each other, empathy was stronger, making it difficult to regard such matters as someone else’s problem.

In contrast, in the case of organic solidarity, the emphasis is less on punishment and more on the restoration of social solidarity.

For example, consider a situation in business where a judge orders payment when a contracted amount has not been paid. The focus is on returning to normal performance and restoring the customer relationship.

Disputes between friends or romantic partners are also handled by civil law, aiming not at deterrence but at fostering cooperation. Modern societies tend to place a greater emphasis on restitutive law compared to premodern societies.

A Perspective on the Interaction of the Entire Society

In organized societies with developed division of labor, individuality, irreplaceability, and interdependence are high. Therefore, there is likely a greater need to regulate relationships. Excessive punishment, expulsion, or violence can disrupt social functioning.

However, as noted earlier, Durkheim did not believe that any society is dominated solely by one type of solidarity. Thus, the balance between both types of solidarity becomes crucial.

Additionally, the examination of integration tendencies based on specific cultural differences is addressed through statistics, such as those in Suicide.

In any case, it is necessary not to focus solely on law but to consider the interactions of various social facts—including religion and the economy—from multiple and holistic perspectives in order to conduct a more valid indirect observation of society itself.

It is, of course, nearly impossible to make society itself entirely visible.

However, I recall Weber’s words that “nothing can be achieved without attempting the impossible.” Sometimes, it may be necessary to set an ideal and adopt an attitude of gradually approaching it.

No society is sustained by religion alone or by the economy alone. Oversimplifying things leads to overlooking many important aspects and increases the risk of misinterpretation.

Even when analyzing phenomena solely through law or religion, it is crucial to remain strongly aware that such analysis reflects only the perspective filtered through the sociologist’s own biases.

In the words of Karl Mannheim, it is essential to maintain a strong awareness of totality. We view phenomena through colored lenses, and we must recognize that we are not seeing things as they are in themselves, nor society itself in its pure form. Given this, it becomes necessary to wear various colored lenses and to expand and integrate perspectives in a way that does not rely solely on any one lens. Mannheim calls this stance correlationism.

References

Recommended Readings

Emile Durkheim「The Division of Labor in Society」

Emile Durkheim「「The Division of Labor in Society」

DK Publishing, Sarah Tomley「The Sociology Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained (DK Big Ideas) (English Edition)」

About the Japanese version of this article

This article is a translation of an article written in [https://souzouhou.com/2024/11/27/durkheim-4-1/]. For detailed references, please refer to this link.

Comments